Sublime Mind, Elegant Solutions

During Arm’s early years, Matt Lee was awakened at 2 a.m. by a call from police. They informed him that the security alarm at the Arm Barn near Cambridge was going off and that the intruder was on the phone with officers.

Lee, the nearest Arm employee with a key, hurried over to find David Seal, one of Arm’s founders, sitting inside at his desk, still on the phone with the Police Control Centre, his bicycle propped against the building. It turns out that David, due to start his holiday the next day, had enjoyed himself at a local pub just after work. He realized after a few wobbles that he couldn’t cycle safely all the way home, so he headed for his second home. But he had neglected one step in de-activating the security system and ended up on the phone with the police, with the alarm blaring in the background.

“I had an old Porsche Targa at the time, and I took the roof out, put David’s bike behind the front seats, and, with David apologizing profusely, I ran him and his bike home,” Lee, former Arm Collaborative Projects Manager and University Program Manager, recalled recently. “After his two-week holiday, he sent me a sincere apology in an email.”

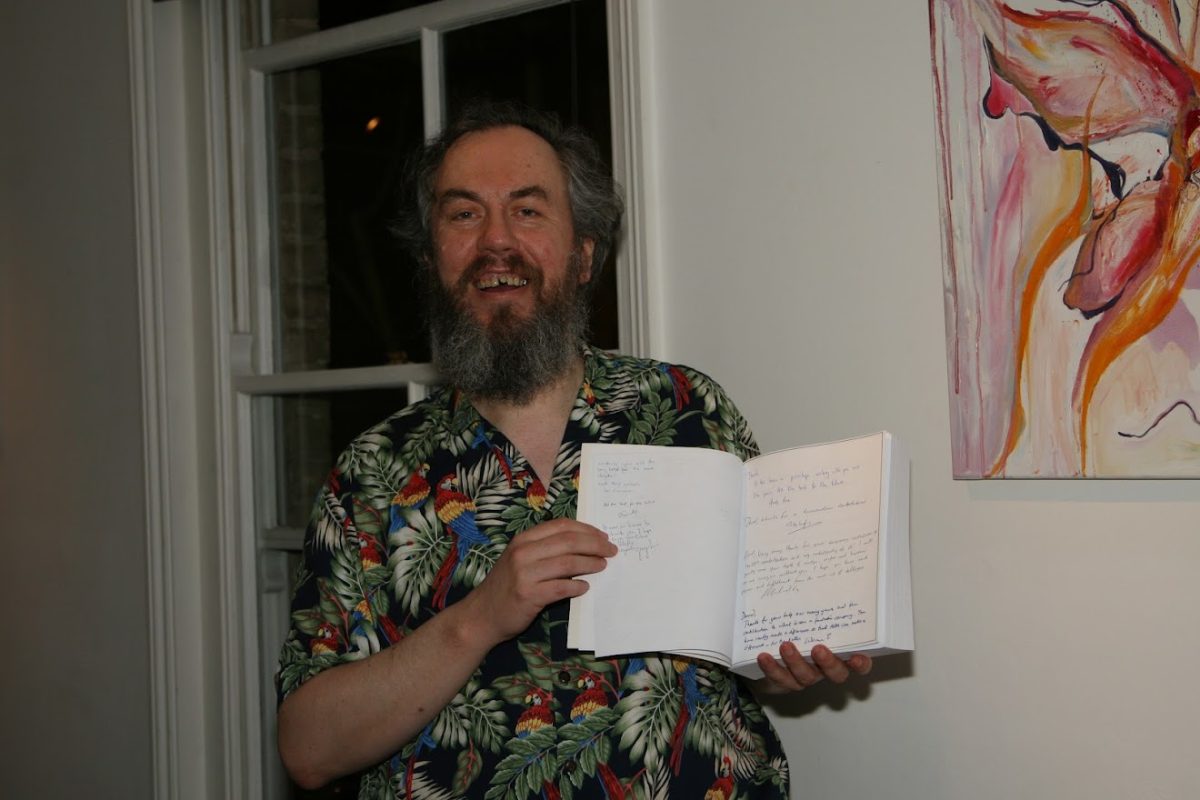

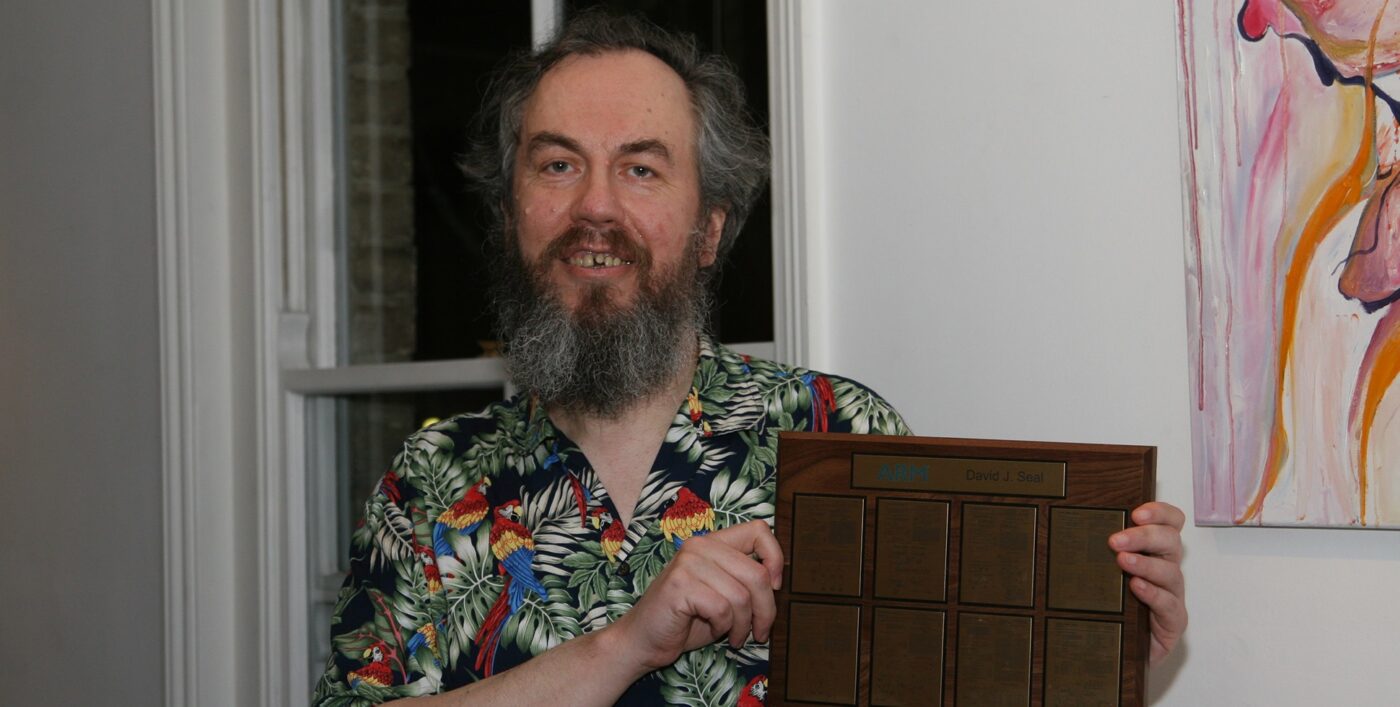

David Seal, described by virtually all his colleagues as a towering intellect and engineer, a dynamic and instrumental force in Arm’s early years and a profoundly kind person and mentor, passed away in December. He was 65.

David received a B.A. in mathematics from Cambridge University. Colleague Sophie Wilson, who, with Steve Furber, created the ARM Architecture in the early 1980s while at Acorn, recalled that David joined that company around 1981-82.

“David initially worked on the BBC Micro Graphics Extension ROM, doing things like the mathematics of rotated ellipses,” she said. “He spent a lot of time working on rasterization primitives, getting perfection in the matter of which pixels are which side of a line.”

He then joined Acorn’s AR&D (advanced research & development), before becoming one of the original people who signed up for “Project A,” the ARM development. There, his main contribution was to the verification and validation of the ISA (instruction set architecture), according to Wilson.

Founders’ days

David was one of 12 Acorn engineers who founded Arm Nov. 27, 1990, in Cambridge, with a processor technology that would eventually change the semiconductor design business and the world.

He played a key role leading the Arm architecture from the founding of Arm, edited the second edition of the ARM Architecture Reference Manual, was one of the first Arm Fellows, and provided vast knowledge and guidance to Arm and the Arm community. He retired from the company in 2009.

“Being lucky enough to give David a lift to and from ARM when it was in the Barn was wonderful because each journey became the most amazing private lesson on a topic,” said Simon Watt, who, for many years, was Arm’s research director. “You’d get onto a topic, and he’d explain about it with clarity and detail, and you’d arrive at the other end feeling like you’d just learned something fascinating. It was like having a personal version of a really good TED talk, tailored just for the audience of the two of us.”

According to Arm Distinguished Engineer Guy Larri, David had a big role in the design of the floating-point accelerator which was used as an option in Acorn desktop computers to speed up floating-point mathematics operations. It was also included in some early system-on-chip (SoC) designs.

Seeing the big picture

And it was at Arm that David’s technical genius flourished. In fact, Tudor Brown, another Arm founder, said in his retirement presentation that “half of Arm’s architecture came out of David’s head.” In the 1990s, David worked with Larri and others on ARM7DMI – the project before Thumb was added to make it ARM7TDMI – on the ARM Architecture Reference Manual, and on ARM8/ARM810.

David worked with Larri and former Arm Fellow Dave Jaggar on adding new multiply and multiply-accumulate instructions and the multiplier-accumulator that was the “M” in the ARM7TDMI, securing several patents along the way.

He called David a ‘custodian’ of the Arm architecture.

“He maintained the details of instruction encodings and took ownership of the Arm Architecture Reference Manual, taking the baton from Jaggar,” Larri said. “He held many patents on architectural innovations over a span of 20 years.”

Years later, he played a central role as Arm transformed its 32-bit architecture to 64-bit.

“The question that came up was, okay, we have a 32-bit architecture with all its nuances, right? And it’s messy (moving to 64-bit),” said Dipesh Patel, Arm CTO. “And by the way, we need to do 64-bit and figure out how we can co-exist with 32-bit. Not for the faint-hearted! David spent a long time thinking about how it could be done. He played an integral role in establishing the foundations for us to build 64-bit ISA into Armv8.”

The legendary Seal-o-grams

It was writing, as much as coding and engineering, that David became renowned for.

“When I first joined Arm in 1993, someone who shall remain nameless, took me aside and said, ‘When dealing with David, it is best to treat him as a batch processor rather than an interactive processor,’” Larri said. The instruction was to submit a job by sending him and email, and wait, perhaps a day or two, for a response. But these responses were epically detailed and beautifully crafted. They became known as Seal-o-grams.

As recently as a couple of years ago, according to Arm co-founder and Distinguished Engineer John Biggs, David produced a Seal-o-gram detailing the odds that three of the first 20 Arm employees – founding CEO Robin Saxby, Jaggar and Glynn Leonard – would share a birthday.

Founder Lee Smith recalled a situation in which a stumped David Seal turned out to be a good thing.

“I convened a small group in 1998 to chew over an idea I had come up with for reasoning mathematically about compatibility between binary code compiled with different options and for different versions of the architecture,” he said. “By 1998, that was posing real problems. That led to ‘build attributes’ for relocatable object code. David helped by agreeing to its mathematical plausibility and – unusually – being unable to think of a better idea! That gave us a lot of confidence.”

Pete Harrod, Director of Functional Safety within Arm’s Central Engineering Group, said he once wrestled with the design of the control unit that orchestrated the progression of the four arithmetic pipeline stages in the FPA, the floating point accelerator. He turned to David for help.

“He came up with the most elegant solution imaginable. It took him a page or more of closely typed text to explain the reasoning behind his design, but the implementation was just a few lines of code. Simply sublime,” Harrod said.

David’s contributions to laying the groundwork for the Arm of today can’t be overstated, according to colleagues.

“Dave was one of the very few people who genuinely deserve large credit for Arm being where it is today,” said Peter Greenhalgh, Vice President of Technology and Arm Fellow. “A great person and always approachable and open to all people and all grades.”

Richard Grisenthwaite, Arm SVP, Chief Architecture and Fellow, said: “David was an utterly inspirational technical leader at Arm. He was an astonishing intellect with an unbelievable level of rigor and precision but tempered with a ready wit and an interest in working with and helping others. He personified that principle that someone who really understands their subject, however complex it is, can explain it in understandable terms to the layman, and used that ability to help set Arm up on its course.” David’s family has created a memorial page, and readers are invited to share their memories and contribute to Cancer Research UK.

Any re-use permitted for informational and non-commercial or personal use only.